This post remains available for posterity’s sake, but a much revised and much expanded version of this translation is available completely for free! The revised version includes translated footnotes, a translated appendix, an expanded introduction, and a map of disputed territory and important locations. You can download a copy in the following formats: Docx — Epub — Mobi — PDF. Or, if you want to throw some money my way, you can set your price for it on Smashwords. And it’s in the public domain!

This post remains available for posterity’s sake, but a much revised and much expanded version of this translation is available completely for free! The revised version includes translated footnotes, a translated appendix, an expanded introduction, and a map of disputed territory and important locations. You can download a copy in the following formats: Docx — Epub — Mobi — PDF. Or, if you want to throw some money my way, you can set your price for it on Smashwords. And it’s in the public domain!

Note: This chapter deals with an incident which occurred in the aftermath of the Uruguayan Civil War, which I just wrote a whole supplementary post about. I recommend reading it before reading this chapter, if you have not already.

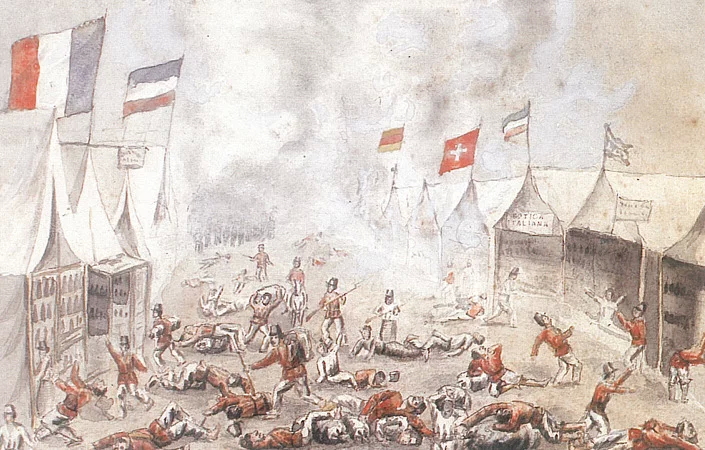

The situation in the Eastern State at the end of 1853 also appeared full of difficulties. In February 1854 the Uruguayan government requested the Empire’s intervention, invoking the 12 October 1851 treaty of alliance (1). Not without much hesitation, our government decided to send to Montevideo a division under the command of General Francisco Félix. No unpleasant event, fortunately, resulted from the presence of that Brazilian force in our neighbor’s capital; but in August 1855 the republic again entered a period of crisis, seeing the president, General Flores, forced to abandon the capital, where immediately a de facto government was formed (2). In this way, the danger of a civil war arose, in which we could see ourselves entangled, along with the Argentine Republic and Buenos Aires. Through all the time of the Paraná ministry the Argentine Republic was divided into two governments: that of the Confederation, whose capital was Paraná, under the presidency of Urquiza, which the thirteen provinces obeyed; and that of Buenos Aires, reduced to the province of Buenos Aires.

Brazil did what was most prudent, given the circumstances: Limpo de Abreu, who shortly before had left the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, was sent to the Plata on a special mission. But before arriving at his destination, the rift—the cause of his departure—was fixed, General Flores having resigned from the presidency, and having been replaced by Bustamente, president of the senate, in accordance with the Constitution.

To this episode Nabuco (3) refers in the following congratulatory message to his colleague from Foreign Affairs: “Y.E., deign to accept my congratulations for the agreeable solution that before your arrival had had the political contention that caused your appointment. Fortune not only accompanies you, but it precedes Y.E.’s steps.”

The following paragraph from an intimate letter to Boa-Vista proves completely the sincerity of the Empire’s politics and the selfless thoughts that animated it. “The policy that we pursued in the Eastern State was not one of balance, but rather one of observation. It was fit, senhor barón, to judge whether the casus fæderis, or cause to comply with our obligation to lend aid to the legitimate government, had arrived; it was fit to know from which part the beginnings of stability would be; it was fit that we would not, beguiled by sympathy, identify ourselves with a foreign party, going along with it—to the detriment of Brazilian relations—in its fortune and adversity, or imposing its will upon the Republic; it was fit to not have the ambitions of the Blancos nor those of the Colorados, a rivalry that was born and appeared after the victory (4); it was fit that Brazil’s intervention was not seen as an imposition, as complicity in the revolutionary movement, as partiality in favor of the Colorados, but rather as a necessity, a desire of all, Blancos and Colorados, as a principle of security for Brazil itself and for the Eastern State. Time, and only time, will show the true character of Brazil’s conduct. Time already vindicates us, and you vindicate us when you say: ‘It is essential that Brazil not be at the mercy of the ambitious of Uruguay.’”

Translator’s Notes

1. Refers to the treaty ending the Uruguayan Civil War, which granted Brazil the right to intervene in future conflicts in the country. In 1854, there was conflict brewing within the Colorado party.

2. This refers to the Rebelión de los Conservadores, a revolt against the Colorado president Venancio Flores by dissidents within his own party.

3. That is, José Tomás Nabuco Jr., the father of Joaquim Nabuco, and a Brazilian politician.

4. The two major political parties that emerged from the Uruguayan Civil War.